IT

EN

ES

FR

IT

EN

ES

FR

These frescoes, crafted by some of the greatest artists of the era, bear witness to the Italian Renaissance and its artistic and cultural evolution.

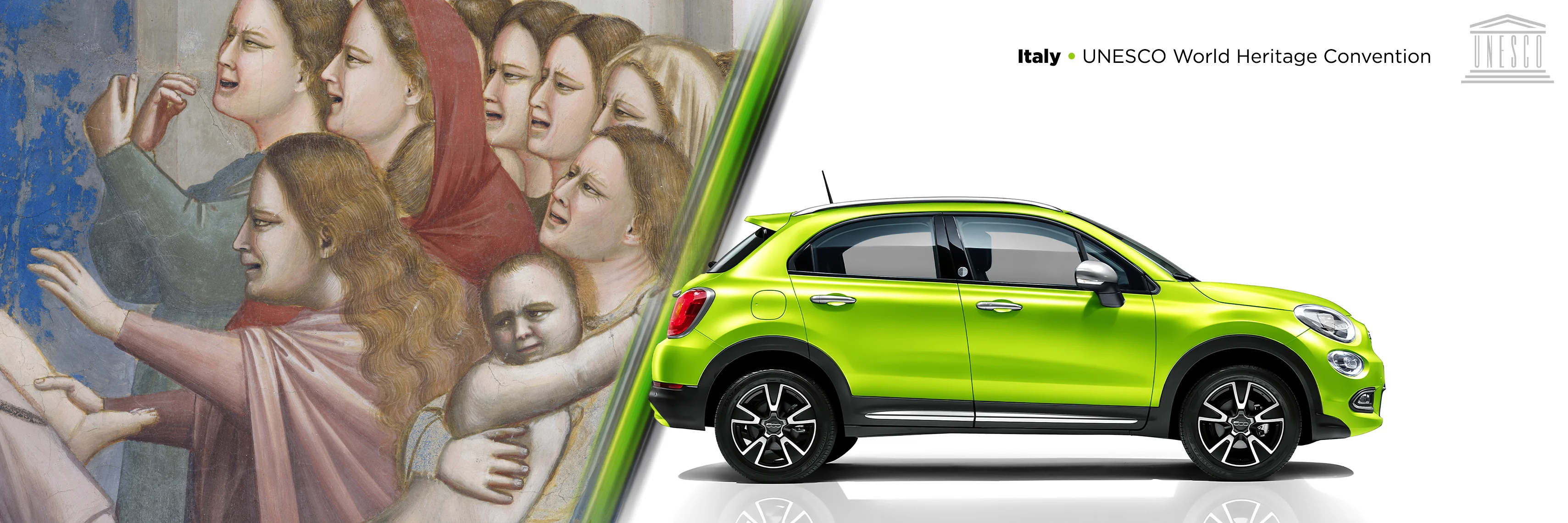

Among the most renowned fresco cycles is Giotto's work in the Scrovegni Chapel. Giotto, considered the father of Renaissance painting, depicted sacred and secular stories with unparalleled mastery, breathing life into characters with human and expressive features, paving the way for a new understanding of art.

Another significant cycle is Guariento's in the Hall of the Giants in the Palazzo della Ragione. Here, the artist painted mythological and allegorical scenes, showcasing his skill in perspective and creating a sense of grandiosity.

Altichiero's fresco cycle in the Basilica of Saint Anthony is equally noteworthy. The artist portrayed the life of Saint Anthony, helping spread the cult of the saint and solidifying his importance in the Catholic religion.

These fresco cycles bear witness to the richness of art and the depth of faith in 14th-century Padua. Inclusion in the UNESCO list is a recognition of the universal value of these works and the importance of preserving them for future generations to continue inspiring and enchanting audiences worldwide.

This property consists of eight complexes of religious and secular buildings within the historic walled city of Padua, which house a selection of fresco cycles painted between 1302 and 1397 by different artists for different types of patrons and within buildings of diverse functions. Nonetheless, the frescoes maintain a unity of style and content. They include Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel fresco cycle, considered to have marked the beginning of a revolutionary development in the history of mural painting, as well as other fresco cycles of different artists, namely Guariento di Arpo, Giusto de' Menabuoi, Altichiero da Zevio, Jacopo Avanzi, and Jacopo da Verona. Collectively, these fresco cycles illustrate how, over the course of a century, fresco art developed with a new creative impetus and understanding of spatial representation.

The fresco cycles are housed in eight complexes of buildings within the old city center of Padua. They illustrate how, over the course of the 14th century, different artists, starting with Giotto, introduced significant stylistic developments in the history of art. These eight building complexes are grouped into four component parts: Scrovegni and Eremitani (part 1); Palazzo della Ragione, Carraresi Palace, Baptistery, and associated Piazzas (part 2); Complex of Buildings associated with the Basilica of St. Anthony (part 3); and San Michele (part 4). The artists who played a leading role in creating these fresco cycles were Giotto, Guariento di Arpo, Giusto de' Menabuoi, Altichiero da Zevio, Jacopo Avanzi, and Jacopo da Verona. Working for illustrious local families, the clergy, the city commune, or the Carraresi family, they produced fresco cycles within both public and private, religious and secular buildings, giving rise to a new image of the city. Despite being painted by different artists for different types of patrons within buildings of varying functions, the Padua fresco cycles maintain a unity of style and content. Within the artistic narrative unfolding in this sequence of frescoes, the different cycles reveal both diversity and mutual coherence.

The property illustrates a completely new way of depicting allegorical narratives in spatial perspectives influenced by advances in the science of optics and a new capacity to capture human figures, including individual features displaying feelings and emotions. Innovation in the depiction of pictorial space involved exploring the possibilities of perspective and trompe-l'oeil effects. The innovation in the depiction of states of feeling is based on a heightened interest in the realistic portrayal of human emotions and the integration of the new role of commissioning patrons who begin to appear in the scenes depicted, and ultimately even take the place of figures participating in the biblical narrative. In effect, the works illustrate the adaptation of sacred art to serve the secular celebration of the prestige and power of the ruling powers and associated noble families.

The Padua fresco cycles illustrate the important exchange of ideas that existed between leading figures in the worlds of science, literature, and the visual arts in the pre-humanist climate of Padua in the early 14th century. New exchanges of ideas also occurred between clients commissioning works and the artists from other Italian cities who were called to Padua to collaborate on the various fresco cycles inspired by scientific and astrological allegories or ideas on sacred history gleaned from contemporary intellectuals and scholars. The artists showed great skill in giving these ideas visual form, and their technical abilities allowed the Padua fresco cycles not only to become a model for others but also to prove remarkably resistant to the passage of time. The group of artists striving for innovation who gathered within Padua at the same time fostered an exchange of ideas and know-how which led to a new style in fresco illustration. This new fresco style not only influenced Padova throughout the 14th century but formed the inspirational basis for centuries of fresco work in the Italian Renaissance and beyond. With this veritable rebirth of a pictorial technique, Padua supplied a new way of both seeing and depicting the world, heralding the advent of Renaissance perspective. The innovations mark a new era in the history of art, producing an irreversible change in direction. The four component parts comprise eight complexes of buildings in the center of Padua – some publicly owned, some privately owned, some secular, some religious – which present an overall shared approach in terms of techniques, themes, dating, and style, and bear witness to new programs of narrative and figurative choices in fresco painting. They illustrate the complete range of the various aspects of innovation in Italian frescoes in the 14th century.

The institutional bodies (Padua City Council, the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities, the University of Padua) that own the different sites have promoted research, maintenance, and restoration work necessary to maintain the various fresco cycles in a good state of conservation. Such work means that each of the single parts can still be read and understood, both individually and in relation to each other. The attributes of the property illustrate authenticity in material, design, in particular workmanship, setting, and, to a certain extent, spirit and feeling in relation to the religious concepts they evoke. The authenticity is further expressed in the inseparable bond between the frescoes and the interior architectural spaces they are part of as well as the architectural construction of the historic buildings.